I created the above videos before I did my lesson Notes On The Guitar, so while I talk about that stuff in the video, I won’t discuss it here. So, let’s start off by looking at the keyboard.

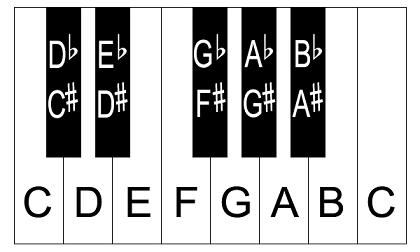

When you move just one note/key over (in either direction) it’s called a “half step”. When you move two notes/keys over it’s called a “whole step”. Take a moment to figure out the order of whole and half steps you get by going from C to C on the keyboard playing only the white notes.

Got it? W-W-H-W-W-W-H? Good! This combination of whole and half steps makes up the major scale. Since we started from a C note, we have a C major scale. If you go through that same combination of whole and half steps starting from a D note, or an E♭ note, or any other note, you will get a __ major scale! Try to figure out the notes in some other major scales. Remember, you never mix sharps and flats in a major scale, and you will always use all 7 letters in order. Some major scales may require double sharps or double flats, in which case it’s probably best to think of the scale as having a different root. For example, A♯ Major would have a B♯, C double sharp, E♯, Fdouble sharp, and G double sharp… that’s a little awkward. BUT, if you call it B♭ Major instead, then you just have B♭ and E♭, which is much easier to think about.

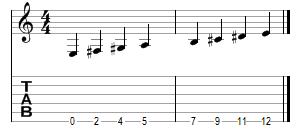

Okay, now we need to play some major scales on our guitar. You may have guessed that a half step is equal to one fret and a whole step is equal to two frets. Well, you guessed right! So let’s try to play an E major scale on the guitar, starting from the open low E string. It will go like this:

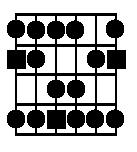

You can play those notes on different strings, which is how you come up with different scale shapes/fingerings. This next shape is particularly useful for figuring out different ways to play chords. It’s a position shape, which means you play it using one finger per fret and don’t move your hand (which is what makes it good for this purpose). Squares indicate the root notes.

Each note in the scale is also assigned a numerical value. The root note (the note from which we start our W-W-H-W-W-W-H pattern) is the 1. Next is the 2, then the 3, and so forth. All of this is covered in more detail in my intervals lesson.

So chords are basically different notes in a scale played simultaneously. Allan Holdsworth humorously compares this to a large family sitting at a table, then having certain members stand up to have their picture taken. “Steven, George, Sarah… Winston or whatever”. It seems silly, but it really is a great way to think about it. (you can watch the video here)

Instead of using names, we’re just going to use the numbers we came up with earlier! So if we play notes 1 3 and 5 of the major scale all at the same time, we get a major chord! In the E major scale we did earlier, we can see that notes 1 3 and 5 are E G♯ and B notes. That means that any combination of E G♯ and B notes is an E major chord!

Chord formulas can also include ♯ and ♭ numbers. For example, a minor chord is built 1 – ♭3 – 5, so we take our E – G♯ – B, but then flat the 3, giving us a G natural note. Now we’ve got E – G – B, which is our E minor chord. An augmented chord is built 1 – 3 – ♯5, which would give us E – G♯ – B♯ (this is one of those situations where it’s actually appropriate to call it B♯ instead of C)

Here is a chart that lists a whole bunch of different chord formulas. Study it. It shouldn’t take long before you start recognizing patterns in how the chords are named. The names aren’t arbitrary; they tell you exactly what notes are in the chord. I remember my very first guitar lesson… it was with a great player named Brad Bischoff. I walked in, played an open G major chord, and said “That’s G major. Tell me why.” He pulled out a chart very similar to the one I created up there and my whole world was illuminated. Having that sort of information helped me progress A LOT faster than my friends (who started playing guitar around the same time). Each week they would come home from their lessons bragging about learning a new chord. I’d just ask “What’s it called?” then figure it out myself. They never wanted to listen to me when I tried to explain to them that their teachers were wasting their time and money by not REALLY teaching them music. They gave the same ridiculous retort every time “We don’t use that theory crap. We don’t want to stifle our creativity.” It took years for them to realize how right I was (and how foolish they were), and how stifled their playing had been by their lack of understanding.