While “Superimposed Pentatonics” may sound fancy and technical, it’s actually a really simple concept that you can use to give your old, tired pentatonic licks a new flair. While this concept can be used with any of the 5 pentatonic shapes, we’re only going to look at the minor pentatonic (1 – b3 – 4 – 5 – b7). We’re sticking to this one because it’s the one that most people are comfortable using. Let’s start off with a lick:

MIDI

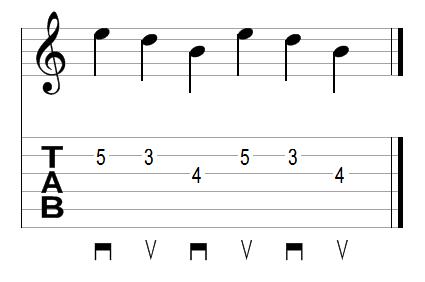

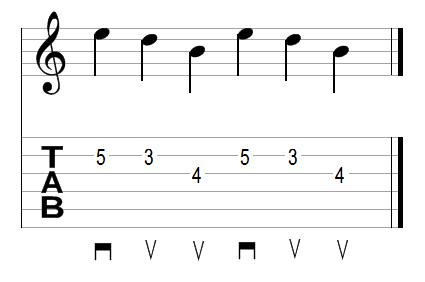

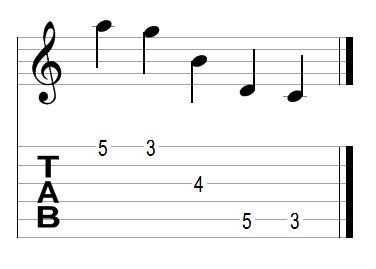

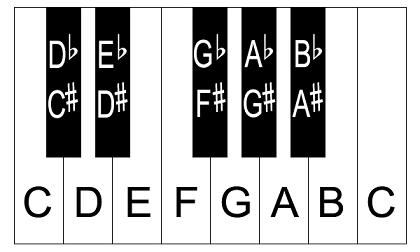

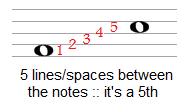

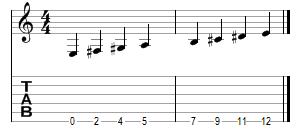

MIDIThis is a typical minor pentatonic lick using the A minor pentatonic shape (start on the 5th fret). Play it over an A- chordMIDI and you’ve got a something you’ve probably heard before (and may even be bored of). So let’s mix it up a bit! Move that whole lick down 2 frets (a whole step). Play it again over the same A- chord.MIDI What happened? It was the same lick, same fingering, but it felt different. By moving the lick down a whole step, you changed each note’s relation to the chord, and ended up with something that clearly implies a Phrygian modality. Take a look at the diagram below and you’ll see how the notes in our minor pentatonic shape relate to the root of our A- chord.

Notice that we don’t play the root of the chord at all in the lick? This gives us a really interesting sound by eliminating players’ tendency to just lean on the root all the time.

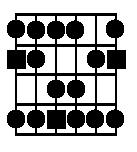

So now you’re probably thinking “What happens if I play a whole step up? or a half step down? What happens if I move it up a whopping 7 frets?” Well I’ve already done all that work for you. I’ve mapped out the minor pentatonic shape in all possible relations to the root. Some of them are a little more difficult to utilize, and some of them sound great right away, requiring very little exploration before you find something cool about the sound. Here are my results, complete with where to start your minor pentatonic shape, what notes these are in relation to the root, what modes they could imply, and what chords you could play the shape over (it’s always okay to just play the triad instead of the 7th chord btw).

- 2 frets up (whole step)

- 2 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 1

- Can be Ionian, Mixolydian, or Dorian

- Play over A, A-, A7, practically anything

- 4 frets up (major third)

- 3 – 5 – 6 – 7 – 2

- Can be Ionian or Lydian with no root

- Play over AΔ7

- 5 frets up (perfect fourth)

- 4 – b6 – b7 – 1 – b3

- Can be Phrygian, Aeolian, or Locrian

- Play over A-7 or A-7(b5)

- 7 frets up (perfect fifth)

- 5 – b7 – 1 – 2 – 4

- Can be Mixolydian, Dorian, or Aeolian

- Play over A7 or A-7

- 2 frets down (whole step)

- b7 – b2 – b3 – 4 – b6

- Can be Phrygian or Locrian with no root

- Play over A-7 or A-7(b5)

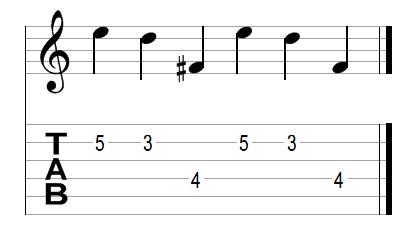

- 1 fret down (half step)

- 7 – 2 – 3 – #4 – 6

- Cleary implies Lydian with no root

- Play over A<Δ7

You’ll notice that a couple of these leave few possibilities in regard to what mode they imply, while others leave things pretty vague. Use this to your advantage! You want to have a Dorian sound somewhere? Take a lick and play it in position then again a whole step up.MIDI BAM! You just hit every note in Dorian! Plus, you got a little sequence action in there… probably had a pretty cool lick to begin with… chances are, you’re starting to sound like somebody that knows what they’re doing, and not just some schmo throwing around minor pentatonic licks.

Of all these possibilities, my favorite is easily the last. Blazing through minor pentatonic licks while suggesting Lydian without ever hitting the root just sounds awesome. You are, of course, encouraged to try out the other pentatonic shapes. They will yield the same note relations, but the shape itself will influence what type of licks you play. For example, I find it really difficult to play really rocking licks using the major pentatonic shape… I always want to play more jazzy stuff with that shape. Whatever you do, try to stay creative, and if you’re ever at a loss for what to do in Phrygian, just drop down a whole step and tear it up!