This is a series that I’ve wanted to do for a long time. I was waiting until I could get myself a Mosrite Ventures II copy (I’m obviously not going to get a real one, as there are maybe only 50 in existence). Ideally, I’d like a Fillmore; Johnny actually played those near the end of his life but they just don’t come up for sale often. Eastwood has one that is reportedly quite nice, but I want to play it first! If something ever pops up nearby, I’ll probably jump on it, but for now, my new G&L ASAT Bluesboy gets the job done. It’s got a fairly hot bridge pickup that lends itself well to the Ramones sound.

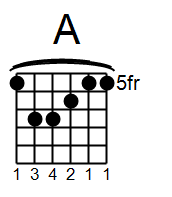

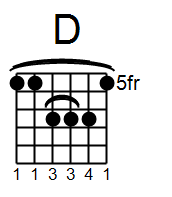

Anyways, in this series, I’ll be showing you how to play EVERY (yes, every) song the Ramones ever recorded, even the covers. We’ll be going through them alphabetically, but first, we need to go over a few things about how Johnny played. While Johnny was a really limited guitar player, he did what he did exceptionally well, and it’s more difficult than a lot of folks assume. For starters: Johnny didn’t play power chords. He played full major barre chords pretty much all the time. He’d occasionally throw in a minor chord, but it was rare. The shapes he used were your basic E and A shape barre chords, as seen below:

Note that when using the “A shape”, you still play the 6th string. This additional fifth on the bottom of the chord really fattens up the sound. While I included the 1st string fingering in the diagrams, you don’t need to worry about getting that top note. Johnny didn’t. You’ll want to check out the video for some additional tips on efficiently switching between these two shapes.

Aside from the chord shapes, the next most important thing about sounding like Johnny is your picking. Unlike the barre chord thing though, everybody knows Johnny only did down strokes. Lots of folks are lazy about this part though, and you shouldn’t be. It makes a big difference in the sound. If you’re getting tired, try lowering your guitar a bit so that your arm is fully extended. Pick from your wrist, not your elbow, and keep at it. It’s tough, but worth it.

I’ll be uploading the lesson for the first song, 53rd & 3rd, soon.